The Transformation of Greek America

Yiorgos Anagnostou

Are we witnessing the end of Greek American identity? Scholars from several disciplines as well as the public outside the academy pose the question. The inquiry comes my way often. As someone who writes about Greek America, I am likely seen as an authority on the subject. Is there a future for this cultural identification? Will it disappear from the US multicultural landscape? Does it matter?

Is the question a sign of premature pessimism? Some see it as out of place. After all, the vibrant presence of US Greek cultural events and practices such as film festivals, preservation societies, radio programs, documentaries, and blogs and social media sites, as well as the proliferation of study abroad travels to Greece for heritage students, create the appearance of a vibrant ethnic group.

In fact, the latest US Census registers a surprising development: a 20 percent increase in the Greek American population between 1980 and 2000, and a further 11 percent growth between 2000 and 2010. How does one explain this development given the low fertility rate of Greek Americans and low levels of immigration from Greece? Sociologists Charles and Peter Moskos propose intermarriage as the “most likely explanation,” with the “non-Greek” spouse being drawn to Greek ethnicity. Greek identity then is embraced by “non-Greeks” and individuals of mixed heritage. In interethnic marriages and among bicultural children, the Greek hyphen offers a desirable source of identification. In these situations, Greek is the dominant identity (1).

But these identifications are often seen as the last gasp of a dying cultural phenomenon. Greek America, I am repeatedly told, is thinning to the point of no recognition. It will soon be a mere memory, a testament of the voracious assimilative power of the US melting pot. In this line of thinking Greek Americans are turned into Americans of Greek descent. Connections with the Greek background will be so tenuous as to ultimately carry little meaning, if at all, in the lives of the people who claim it. The belief in an inevitable dissolution finds ample supporting evidence in the reduced Greek affiliations of a large sector of the third generation and beyond. Is Greek America doomed? Are we writing about an ethnic group that is disappearing as we speak?

Yet another version of the narrative about cultural thinning also comes up in conversations. It points to the privatization of cultural identities, as new technologies in communication enable the expression of identity without requiring an ethnic community. In this context, a person can cultivate Greek connections in the privacy of the home, by listening to music, following the news, and reading. Or through personal pursuits such as travel. Cultural elites and global professional nomads, as well as a sector of the middle class, embrace a cosmopolitan ethos wherein a person’s Greek identity is no more than a tiny fraction of the multifaceted cultural self. The same person might dance her heart out to Latin rhythms, reflect on Baudelaire’s “Ennui! That monster frail!” and perhaps find an answer in Manos Hadjidakis’ Gioconda’s Smile. Cultural eclecticism is the name of the game. One could be in love with Paris in autumn, New York in spring, and occasionally enjoy Athens. What is the import of Greek culture in the lives of global Greek architects, artists, writers, and other professionals born outside Greece? We do not have a good answer to this question.

But does this hybridity and eclecticism naturally signal extinction, or does it point to something else that we cannot readily recognize? Is the language of identity thinning appropriate? I myself recoil at predictions about the cultural future of an ethnic group. If someone in the early 1920s—an era of militant US xenophobia—predicted, in a flight of imagination, that Americans would be flocking to Greek festivals in Charlotte, North Carolina, or Dayton, Ohio, in the 1990s, he would have been the subject of derision or dumbfounded disbelief. The 1920s were an era when hyphenated identities—Greek-, Italian-, or Polish American, for example—were rejected as un-American; the idea of a public Greek American festival was seen as an affront to the nation. With no recourse to knowing how history will unfold, predictions about cultural futures engender the risk of their own undermining. As Dan Georgakas aptly notes: “Thinking about the next fifty years is problematic but essential” (2).

What is unsettling about these predictions of Greek America’s inevitable demise is their rigid finality, their teleological assuredness. More than once I have encountered this recalcitrant certainty in conversations when my counter-evidence is summarily dismissed. These are moments of epiphany that illuminate the vast gulf between the guiding assumptions of the academy and the public regarding social life. The prediction of disappearance, for instance, presumes the idea of Greek America as a whole, a shared culture. Consequently, the disintegration of some of its parts—say, language loss—are seen as a preamble to final collapse.

Greek America is undoubtedly undergoing a dramatic transformation. Privatization of identities, multiple cultural affiliations, secularization, intermarriage, cosmopolitanism, global citizenship, and assimilation all work in a centrifugal manner that undermines its conventional ethnoreligious identity. We understand this landscape only partially as the number of scholars working on these topics is no match to the intensity and density of social changes that ripple through this field. As I have written elsewhere, there is an explosion in Greek American cultural production—standup comedy, popular history, autobiography, blogs, poetry, and literature—that remains largely unexamined. Scholars, as I have argued elsewhere, are far behind (3).

It is possible that what the public sees as an impending cultural extinction is in fact Greek America’s profound remaking? This transformation is emergent and therefore difficult to grasp, as our available categories—such as ethnic community or ethnic culture—are inadequate to capture the unfolding phenomena. In the absence of a language to help us name, discern, and comprehend these transformations, many resort to the vocabulary of extinction. The old is undergoing a substantial rearrangement of its elements; aspects of it are even disappearing. The new has not yet taken a discernible form. The challenge is for us to understand these multifaceted developments. Who says that the practice of Greek American studies lacks excitement?

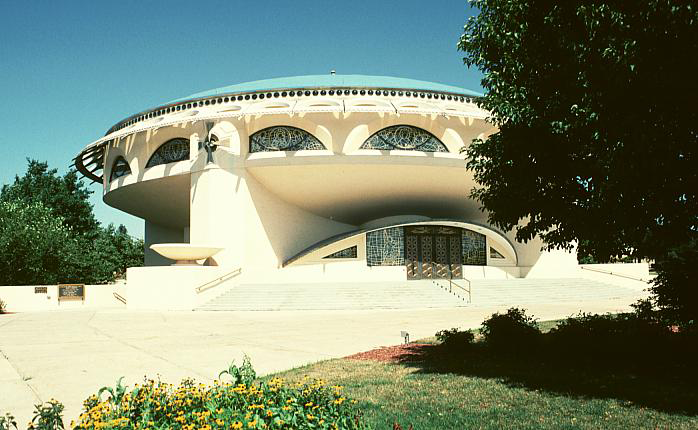

A moment of radical transformation in Greek Orthodox architecture dating as early as the 1950s; architect, Franl Lloyd Wright.

"This church designed for the Greek orthodox congregation in the suburbs of Milwaukee was one of Wright's last commissions."

Notes

1. Moskos, Peter C., and Charles C. Moskos. 2014. Greek Americans: Struggle and Success. 3rd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. With an introduction by Michael Dukakis.

2. See, Dan Georgakas. 2016. “Greek America: The Next Fifty Years.” AHIF Policy Journal. Spring 2016. Accessed 1 January 2017. http://ahiworld.org/AHIFpolicyjournal/pdfs/Volume7Spring/06georgakas.pdf.

The essay takes up the question of cultural revitalization, recommending ways for communities, organizations, and individuals to contribute toward this goal. It deserves careful reading and wide circulation.

3. See, Yiorgos Anagnostou. 2010. “Where does ‘Diaspora’ Belong? The Point of View from Greek American Studies.” Journal of Modern Greek Studies, Vol. 28 (1): 73–119.

(first published in BRIDGE magazine, 9 March 2017)

Bridge, 9 March 2017

Yiorgos Anagnostou is Professor of transnational and diaspora modern Greek studies at The Ohio State University. His work is interdisciplinary and has been published in a wide range of scholarly journals (for a selective bibliography see, http://www.mgsa.org/faculty/anagnost.html). He is the author of Contours of White Ethnicity: Popular Ethnography and the Making of Usable Pasts in Greek America (Ohio University Press, 2009), now under translation into Greek (εκδόσεις Νήσος, 2017). He has also published two poetry collections, «Διασπορικές Διαδρομές» (Απόπειρα 2012, http://apopeirates.blogspot.com/2012/04/blog-post_20.html), and «Γλώσσες Χ Επαφής, Επιστολές εξ Αμερικής» (Ενδυμίων 2016, http://endymionpublic.blogspot.com/). He is the co-editor of the online Ergon: Greek/American Transnational Arts and Letters (http://ergon.scienzine.com/). He writes for Greek and Greek American media, and occasionally blogs on Greek America (http://immigrations-ethnicities-racial.blogspot.com/), and diaspora poetry (http://diasporic-skopia.blogspot.com/).

Greek America is undoubtedly undergoing a dramatic transformation. Privatization of identities, multiple cultural affiliations, secularization, intermarriage, cosmopolitanism, global citizenship, and assimilation all work in a centrifugal manner that undermines its conventional ethnoreligious identity. We understand this landscape only partially as the number of scholars working on these topics is no match to the intensity and density of social changes that ripple through this field. As I have written elsewhere, there is an explosion in Greek American cultural production—standup comedy, popular history, autobiography, blogs, poetry, and literature—that remains largely unexamined. Scholars, as I have argued elsewhere, are far behind.