The Parthenon, The Elgin Marbles: A Personal Reminiscence

George T. Karnezis

For me, growing up Greek-American meant, among other things, that there was a place called "the old country," sometimes called the patrida, the birthplace of my Dad and of my Mom’s parents, and that all the clothing that my brother and two sisters had outgrown were to be saved for poor children living there. It also meant that the bedroom I shared with my brother got pretty cramped with the addition of that new single bed needed to accommodate a continuous stream of dad's brothers, our uncles and their sons, dad's nephews. (We never thought to ask why our aunts or our cousins' sisters remained in Greece.) Having this Greek connection also meant weird surprises, like the time I opened our small bedroom closet door and saw a large serving bowl covered with a towel. "What's this?" I asked. My mother answered with a sigh: “Theeo Stelio's yogurt. Not to be disturbed.”

I don't recall that any of my friends growing up with me on Chicago’s South Side in the '50's were housing immigrants the way we were, and my brother and I figured it was a pretty big deal because, as we were told, you had to write your Senator or Congressman for permission to bring relatives like these to America. I don't know if my brother and I thought growing up with them made us special, but, while we accepted living in more cramped quarters, we resented being forced to attend Greek School 3 days a week. This extra schooling after regular school stole that precious free time that others (except for the Jewish kids attending Hebrew School) could enjoy. The school, an assemblage of desks in St. Spyridon church’s basement “hall,” was controlled by an aged, overweight teacher whose face taught us what female Tyrannosauruses must have looked like. Her name was Kyria F, and she, unlike our regular school teachers, had permission to pull nastily on our tender ears whenever our error rate in taking down her dictation aroused her anger, which happened quite often.

There were probably pictures or drawings of the Parthenon in the books we used in Greek School, but none made any impression. These same books may have also contained an essay or a story about the Parthenon, but I don’t recall. After all, we were never asked to translate anything we read. Our job was to read aloud, pronounce correctly, take dictation and hope we got things right enough to escape a slap or an ear pull. If someone had mentioned The Elgin Marbles to me I’m sure the first thing that would have come to mind would have been a new brand or type of marbles to be tested on my school playground. It would take some time before I could appreciate the fact that “The Elgin Marbles,” like “The Berlin Painter,” were quite misleading titles, and that a real education could help you understand how this was so, especially with respect to things Greek.

Nevertheless, I do recall two things from my childhood about the Parthenon. They both involve images of that famous structure. My father owned Ted’s Liquors, a combination small bar and liquor store on east 79th Street. Behind the bar was a colorful embroidered image of the Parthenon. It was oval, about the size of a basketball, and lived at Dad’s store because Mom had refused Dad’s wish to have “that thing,” which she called “gaudy,” on display in our apartment. Dad had bought it as a souvenir of his first return visit to Greece, a trip also made famous for us by the fact that our very own father had been among the passengers on The Queen Mary’s Maiden Voyage. He had left Greece just after World War I, having just turned 18. I recall my Theeo Stelio telling us that his mother, our Yiyia in Greece, had worried that Theodore, her eldest of four sons, was most at risk of being drafted for something called the Balkan Wars.

The second and most vivid Parthenon image was made possible by the fact that Dad had used this trip as an excuse to purchase a hand-held movie camera. Suddenly the Parthenon assumed a real presence for us. We watched that silent film of Dad, smartly dressed in a suit and tie, taking a solitary stroll toward us on a windy day amidst the Parthenon’s sunlit columns. Completely absorbed by the ruin, he appeared unaware of the camera, resembling, as some viewers would often note, a potential buyer inspecting this famous property. “The Parthenon,” we joked, “starring Dad from Karnezis Real Estate!” I recall one viewing where a relative had directed our attention to the scaffolding for workers doing repairs, “It’s like this rich American boss is checking up on those guys to make sure they’re doing the job right.” Dad took all this joking well. Though not usually demonstrative of his feelings, he appeared to enjoy his newfound stardom.

I recall that during one viewing, Dad told us a story we found hard to believe. At one point Greece was fighting. The retreating enemy had to take shelter in the Parthenon, and they were running out of ammo. The Parthenon’s columns had lead in them, and the enemy decided to break up the columns and extract the lead to manufacture bullets. According to this story, when the Greeks learned of this, they sent a note to their enemy: Don’t do that; we’ll send you the ammo. As children, we could hardly believe this, and I remember telling the story to someone who scoffed at it. Heck, just make them use up all their ammo and that’s it for them, said the skeptic. Years later I learned the story was true.

Fast forward now to the last year of the twentieth century. I am in London teaching two semester long courses to students from a consortium of American colleges. I am offering two courses which would take advantage of the resources of London and other places in the UK. One, British Culture and Classical Antiquity, would explore how the British fashioned or defined themselves relative to a Greco-Roman world. I invited students to consider how British institutions, politics, education, literature, art and architecture, could sometimes be understood as products of Britain’s conversation with Classical Antiquity. The other course, Public Discourse in the UK, would help students understand the practices of British Media and the conduct of politics or matters of public interest. Happily, since the question of the Marbles’ proper place still received media attention, including a lively televised debate which invited a viewer vote on the matter. So preparing for both courses afforded me more opportunity to study the Parthenon, helping me understand how looking behind those images of it familiar since my childhood offered me a history worth knowing. That history, particularly with respect to Parthenon’s pediments or metopes (routinely mislabeled “The Elgin Marbles,”) offered us a complex and controversial site involving questions of cultural identity and/or ownership. Decades after viewing my Dad’s film I’d like to think I was honoring his habit of looking curiously at the remains of the past, inspecting remnants of Antiquity that reveal a history always worth revisiting. Because of this teaching opportunity I also had the good fortune of meeting Eleni Cobitt, the founder of the Committee for the Reunification of the Elgin Marbles. She told me how her late husband, James, a well regarded British architect, had climbed some scaffolding like that in Dad’s movies, and had concluded that Elgin’s removal of the metopes had, in fact, severely damaged the structure.

* * *

When you enter the room in the British Museum that houses the Parthenon frieze, you can’t help feeling that all those clichés about classical art – its balance, serenity, and energy—suddenly become a necessary vocabulary for describing what you’re seeing. Perhaps I imagined it, but when I visited this room several times during that stay in London, even the lecturing docents seemed to be delivering their observations to eager listeners in more than the usual reverential tones. Somehow this permanent exhibit seemed a gift to the world, lifted into aesthetic space for quiet contemplation and study. Here was our inheritance, here we could understand Shelly’s observation that “we were all Greeks,” or Byron’s leap into the Hellespont and his heeding that fatal call to arms of those Modern Greek rebels against their Turkish oppressors. Focusing on one part of the frieze depicting a resisting bull being led to sacrifice, we might even see, if we yield to the gentle expert voice on the Museum’s audio guide, the sculpture that prompted Keats’s image of “that heifer lowing at the skies” in his famous “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

Such an aesthetic experience would have been less possible in this room had it not been for the special generosity of a British millionaire, William Duveen, whose name graces this gallery which he financed to house these sculptures, gathered together at last and properly displayed in their own room since 1962. Properly, I say, because such a display confirms these figures not merely as artifacts worthy of preservation and exhibition, but as works of art deserving a gallery dedicated exclusively to them. Duveen’s generosity might be considered a twentieth century chapter in the continuing history of British affection for classic Greek sculpture, especially for these which, over a century and a half earlier, had been brought to England through the efforts of Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, and the eleventh of Kincardine, Scotland. Scotland, that part of the Empire so smitten with the example of Greek architecture that in the nineteenth century it mounted an effort, which ultimately failed, to reconstruct the Parthenon on a high hill overlooking Edinburgh.

Lord Elgin’s name remains as a label for these marble sculptures that once adorned the Parthenon’s pediments and made up its interior frieze. There was, however, as I wished my students to note, some unpleasantness surrounding the British Museum’s acquisition of these objects, some question about whether Elgin was not so much their savior as a thief whose “rescue” of them also did considerable damage to the Parthenon. Any British Museum docent granted that a “controversy” persists and that, yes, it’s understandable that Modern Greeks are upset over the sculptures’ removal and plead for their return. British replies are not wanting. For instance, in his The Sculpture of the Parthenon, P.E. Corbett rehearses the tale of how the temple had been subjected to considerable abuse and even direct attack by fanatical early Christians, until Lord Elgin, taking advantage of his appointment as Turkish Ambassador in 1799, allegedly obtained authorization to remove numerous pieces from the remaining structure, succeeding thereby “in rescuing a substantial quantity of sculpture, much of which had fallen from the Parthenon.” The Museum’s audio CD assures me Elgin was a rescuer and that after his long labor, “the marbles came to Britain,” a phrasing that still strikes me as disingenuous in leaving the impression that these works somehow migrated to England under their own power, and that questions concerning Elgin’s authorization and his clumsy efforts while removing them no longer arose.

As I was to learn with my students, the story of the Elgin Marbles becomes more complicated and interesting with further research. It’s not just the fact that the very naming of these sculptures “The Elgin Marbles,” as required by British statute, grants their ownership to the country that so named them, and honor to the man who, if we follow the narrative on the CD, “rescued” them. To look deeper into the question of ownership, we needed to leave the hushed atmosphere of the Duveen Gallery with its abbreviated tale of their acquisition, and enter into a messier and more contentious world of history and cultural politics. In doing so, we would do greater justice to the complex way that a tradition (in this case, Greek antiquity) gets made, and to how nations like Great Britain and modern Greece position or invent themselves and their culture by their relations with each other. In complicating matters appropriately, we learned how art and its preservation in a museum, however much it sought to enlighten and inspire us, can often involve questions that are not merely aesthetic. A sufficiently complex narrative about the Parthenon’s frieze, suggests how such monuments don’t simply “appear” as exhibits; they can sometimes come to be exhibited amidst considerable controversy which has yet to subside. (One look at website of The British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles is sufficient evidence of the continuing contentiousness surrounding the proper place for these sculptures.)

* * *

Let us return to Corbett’s book on the Parthenon sculpture. It begins with a reasonable caution: while we can “enjoy and appreciate” such art “without regard to its original setting. . . such an approach is needlessly limiting” if it ignores the original purpose of the art. Accordingly, Corbett offers us some background necessary for deepening our understanding of what such works can mean once we reconstruct the original physical and cultural setting that alerts us to their civil and religious import. And yet, however helpful Corbett’s contextualizing of the frieze may be, it does not prompt me and my students to ask why these sculptures should have been of such interest, not only to Lord Elgin but also to his many competitors, especially the French. Answering that question takes us down some interesting roads in European aesthetic and political history. Such broader contextualizing invites us to observe France and Great Britain vying for supremacy in Europe and the Mediterranean, both sometimes courting the allegiance of Ottoman Turkey even though they could see how that Empire was already showing symptoms of becoming “the sick man of Europe.”

Lord Elgin enters this scene as an ardent admirer of classical antiquity, an art collector who believes that England’s cultural and artistic reputation could be enhanced if only these treasures from antiquity could be carefully studied to yield those eternal principles for the creation of great art. Still, he might have hesitated in his quest had he foreseen that Napoleon, who coveted these same statues for the Louvre, grew so enraged at the prospect of Elgin’s having beaten his own emissaries on a mission to recover them, that he would finally place him under house arrest and then ultimately imprison him during hostilities between France and England. But no matter. Elgin finally succeeded, and it is reasonable to believe his motivation stemmed from his role as an international figure bent on outcompeting the French for this valuable material possession of classical antiquity, thereby claiming Great Britain as a more worthy curator and inheritor of classical art.

But that is not all. As Artemis Leontis’s Topographies of Hellenism makes quite clear, amidst all this competition, the Modern Greeks become those little-known others who dared to assert their claim as inheritors. A short tale is enough to illustrate how these people without a real nation were, in the eyes of many, a competitor scarcely worth acknowledging. On one occasion, when an ancient statue was removed from Eleusis, a riot erupted. The Greek peasants regarded the work as sacred and feared that its removal would affect the harvest. No matter. The statue was removed. And Elgin’s response, as cited in Theodore Vrettos’s The Elgin Affair, was that “The Greeks of today do not deserve such wonderful works of antiquity. Moreover, they consider them worthless. Indeed, it is my divine calling to preserve these treasures unto all ages.”

As Corbett reminded us, it is important to situate works in their original setting. On the other hand, time passes and works continue to exist in settings which, in the case of the Parthenon frieze, clearly have no bearing any longer on their meaning and value for some people, like those aesthetically insensitive Greek peasants. Instead, we have those wealthy Europeans who, granted privileged entry into such works’ meaning, claim proper ownership rights.

This tale is not atypical; acquisition of antiquities often meant not only their appropriation, but also the denigration of those people who, allegedly, had so devolved, that they were no longer capable of understanding and appreciating the treasures of classical civilization that happened to exist in their homeland. Of course it’s worth emphasizing that since there was no Greek nation, the idea of a Greek identity, while quite real as an experience for modern Greeks, had to be conceived without internationally recognized nationhood. For those Greek peasants, however, that statue clearly connected them to something from their past. But it was, at least from Lord Elgin’s perspective, a foolish, sentimental and, it’s fair to say, wrong connection. The right connection could only be determined by those who knew better. Thus the statue was removed from Greek soil and rests now in a corner of the Fitzwillian Museum in Cambridge, England.

For me and my students, the question of who acquires, “owns,” and even names the Parthenon Frieze was best answerable by constructing this more detailed narrative, one informed by a deeper sense of history and impressing us with how the question of ownership is linked to world powers’ competing claims of entitlement and, indeed, their sense of themselves as chief characters in a grand narrative of western culture, where they also compete as arbiters of high culture. Nonetheless, any Elgin narrative should also remind us that even his contemporaries had doubts about the legitimacy of his “acquisition.” Perhaps the best-known critique appears in Lord Byron’s Child Harold, an attack that also targeted others who followed Elgin’s example. Indeed, according to Christopher Hitchens’ The Elgin Marbles, part of Byron’s poem was so scurrilous it had to be excised from publication. But Byron remained outraged, and in his shorter poem, The Curse of Minerva, he seeks to separate the Scottish Elgin’s “deed” from what a true Englishman would have done, imploring the goddess Minerva (Athena) not to blame England as guilty by association:

Perhaps some lesser known words from another of Elgin’s contemporaries, H. R. Williams, an engraver and author of travel books on Italy and Greece, are also worth noting. Cited by Hitchens, they capture what has been lost since the frieze’s removal from that ancient temple that my Dad appeared to be scrutinizing so carefully. Williams’s words would have struck home for him, and perhaps for many fellow Greek travelers of both his and subsequent generations who are curious enough to question what’s missing from the Parthenon: “What can we say to the disappointed traveler who is now deprived of the rich gratification which would have compensated his travel and his toil? It will be little consolation to him to say, he may find the sculptures of the Parthenon in England.”*

*Note:

Defenders of Elgin’s claim to have rescued the sculptures from further damage must also answer those who insist that further damage to them resulted from Duveen’s wish that they be “cleaned” by British Museum so as to restore their allegedly pristine whiteness. See especially Mary Beard, The Parthenon, pgs.168 ff.

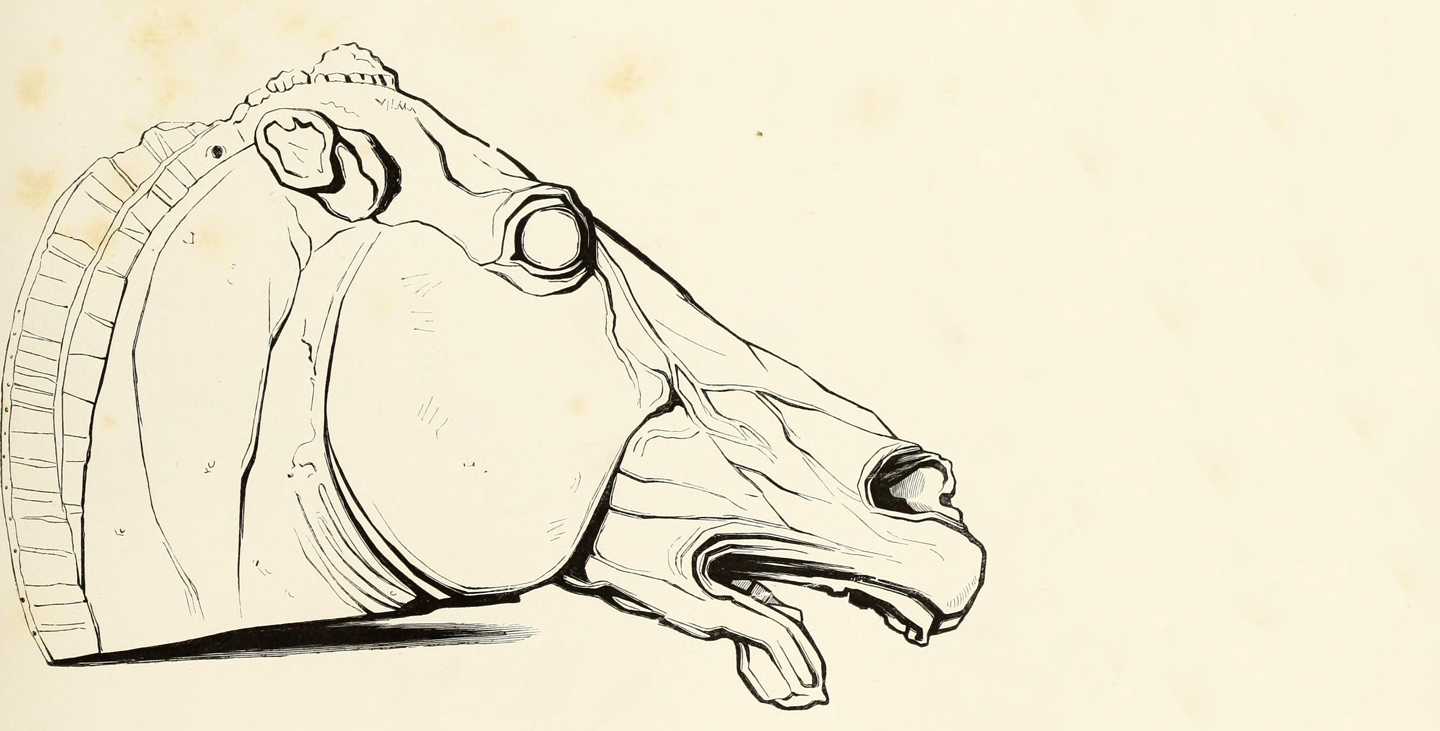

Elgin Marbles, engraving, London 1853 (detail).

Wikimedia commons.

Further Reading:

- Beard, Mary, The Parthenon, Revised edition (Harvard University Press,2010)

- The British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon (www.parthenonuk.com)

- Cook, B.F. The Elgin Marbles, (British Museum Press, 1997)

- Hitchens, Christopher, The Elgin Marbles, Should they be returned to Greece? (Verso, 1997)

- Jackson, Donald D. “How Lord Elgin Won-Lost his Marbles,” Smithsonian, (Dec. 1992)

- Leontis, Artemis, Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland, (Cornell University Press, 1995)

- St. Clair, Lord Elgin and the Marbles, (Oxford University Press, 1967)

- Vrettos, Theodore, The Elgin Affair, (Arcade, 1997)

Note:

An earlier version of this paper was presented at a conference of The Association of General and Liberal Studies Association in October, 2001, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon.

(first published in BRIDGE magazine, 25 June 2017)

Bridge, 25 June 2017

Born and raised on Chicago's South Side, George T. Karnezis is a mostly retired college teacher of rhetoric, literature, and a variety of interdisciplinary courses in undergraduate and graduate Liberal Studies Programs. He is also adjunct professor of English at Portland State University. (Georgetkarnezis@gmail.com)

Perhaps some lesser known words from another of Elgin’s contemporaries, H. R. Williams, an engraver and author of travel books on Italy and Greece, are also worth noting. Cited by Hitchens, they capture what has been lost since the frieze’s removal from that ancient temple that my Dad appeared to be scrutinizing so carefully. Williams’s words would have struck home for him, and perhaps for many fellow Greek travelers of both his and subsequent generations who are curious enough to question what’s missing from the Parthenon: “What can we say to the disappointed traveler who is now deprived of the rich gratification which would have compensated his travel and his toil? It will be little consolation to him to say, he may find the sculptures of the Parthenon in England.”